Feed Tompkins Part 5: Addressing Food Insecurity Means Tackling Housing Crisis, Low Wages

Feeding Tompkins Part 5: Why addressing food insecurity means tackling the housing crisis, low wages

ITHACA, N.Y. — Almost 15,000 Tompkins County residents are food insecure and there is virtually no plan in place in local governments to directly tackle hunger. Feeding people is left to local non-profits who are run almost entirely on grants and charity. Meanwhile, public officials chip away at issues, such as housing costs and wage increases, with the goal of eventually leaving people with more money in their pocket throughout the month to buy food.

“I think we should have a role in food security. I don’t think were doing enough,” Mayor Svante Myrick said about the city of Ithaca.

Myrick said there is no city funding set aside specifically to address hunger. As far as written policy goes, food security was addressed in the city’s recently finished Comprehensive Plan, which called for ” a more fully sustainable and locally-based food system that makes nutritious food available, affordable, and accessible to everyone.”

“Even that still was aspirational. It said what we should do. It didn’t say how we should do it,” Myrick said.

Aside from that, one of the city’s biggest direct roles in food security is acting as landlord for places like the Ithaca Farmer’s Market and the Downtown Dewitt Farmer’s market, which are provided at no or low-cost. There was also the contentious win in 2016 to allow a limited number of people to own chickens within city limits.

For the most part though, the city has made no direct moves toward achieving their goal of food security for every person in the city where, excluding students, nearly a quarter of people live in poverty. Single mothers with children under five years old have a 100 percent poverty rate in the city.

But Myrick is considering ideas that could help fill the gaps in providing food for people, some of which partially based with what helped him and his family when he was growing up in poverty in rural Earlville, New York.

“My mother, when she had us, was working two jobs and raising us, at times for months at a time, in homeless shelters,” he said.

Pantries, food stamps, and soup kitchens were essential to keeping the family fed. So were the chickens at his grandparent’s home, and the vegetables and fruit that grew there and at the home he shared with his mother and siblings. Corn, apples, rhubarb — Myrick said the family froze what they couldn’t immediately eat so they could have food in the winter.

It’s that kind of urban farming that could help alleviate, albeit not eliminate, hunger locally. He pointed to areas at Cass and Stewart parks, along with land by the Ithaca Skate Park near Wood Street, that could work for urban farming. But state regulations dictating the use of park land create immediate, though not permanent, barriers to those ideas.

The best way to tackle hunger then, he said, is by tackling two other major issues in the county: living wages and housing.

Tompkins County Legislator Anna Kelles, District 2, said, “Understanding the relationship between housing, income and nutrition — that triad is extremely important, so in the county, we’re working on all three of those pieces.”

Like the city, Tompkins County has no written policies directly about food insecurity, though some initiatives that encourage collaboration between existing non-profits exist. No funding is directly set aside for food security, but Kelles said funding is allocated for organizations like the Ithaca Children’s Garden and the Cornell Cooperative Extension, the latter of which helps run the Healthy Food for All program, which provides farm shares to 200 families and trains people about how to grow their own food.

Kelles said the intent behind funding organisations or initiatives is to not needlessly “recreate wheels that already exist” when places like Loaves & Fishes, Healthy Food for All, the Friendship Donation Network, and the Food Bank of the Southern Tier already exist.

A matter of cents

In general, Kelles said, people first budget for necessities like housing, heat and transportation to work or school before they spend money on food.

“Without that ability, food is one of the first things to go because having shelter over your head is typically prioritized if it can be,” she said.

In Ithaca, the struggle to afford housing has only become harder over the last nearly two decades.

The Ithaca Voice previously reported:

In 2000, median rent across Ithaca city was $574/month, and median income was $21,441/year. In other words, Ithacans were spending approximately 32 percent of their income on rental payments, which is slightly above the generally agreed upon 30 percent guideline.

For the years 2010-2014 – the most recent housing data – median rent in Ithaca city had skyrocketed to $989/month, with median income rising to $30,318/year. Now, Ithacans are spending approximately 39 percent of their income on rental payments, which is significantly inflated above the recommended 30 percent.

A 16-year movement: median Ithaca rent prices nearly double, people pushed out

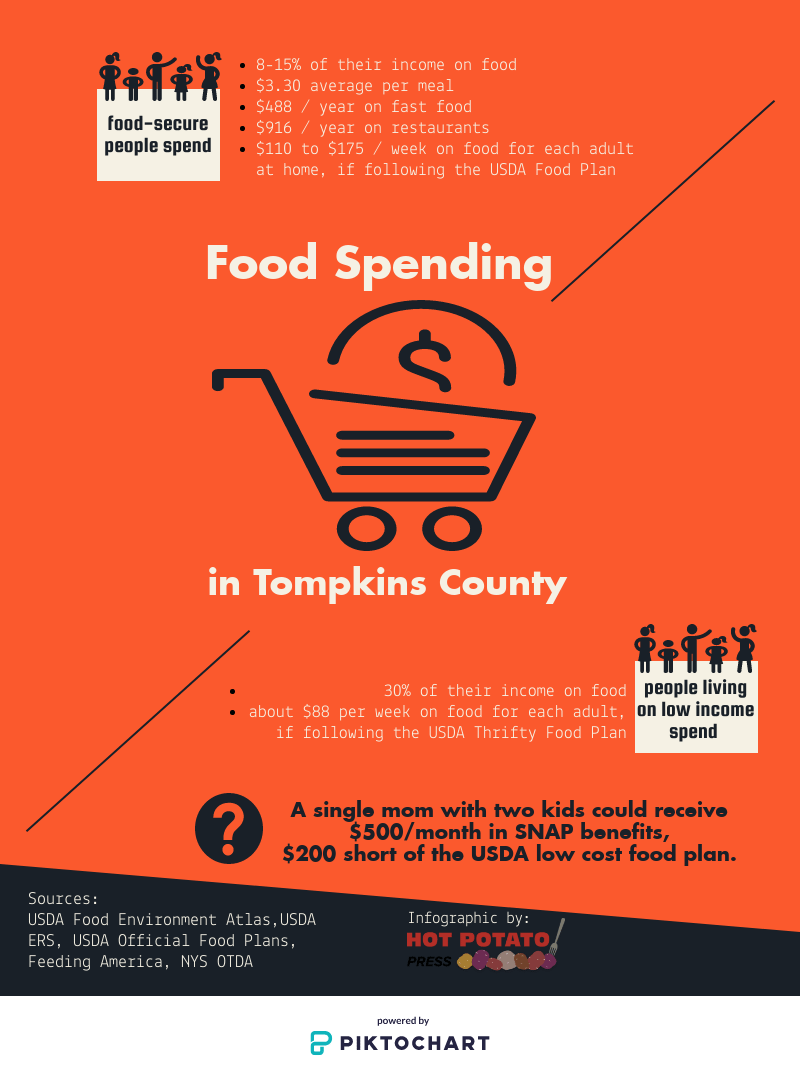

That means some people’s food choices come down to a matter of cents. People living on low-income budgets spend about 30 percent of their income on food in contrast to food secure people who spend 8 – 15 percent of their income on food. That means the only reasonable choice for people living with food insecurity is often calorie-heavy junk food, which is less expensive than nutritious food.

Kelles said apples, for instance, can cost from 50 cents to a dollar, or even $1.25 if it’s a large apple. For the same price, she said, someone can but a meal at a fast food chain. It’s not the healthy option to make, but in terms of calories, a burger or burrito is more likely to make a person feel full for a longer period of time.

The same can be said for other cheap food, like canned vegetables, fruit cups, soda, or cookies. The nutritional density of those items is very low while sugar content and sodium is high. Kelles said the disparity between nutritional calories and empty calories that people living in poverty consume is directly linked to higher rates of obesity in low-income communities. That, in turn, leads to health problems, further widening the economic gap between people.

Myrick said the issue of people’s nutrition being determined by a matter of cents carries over to every aspect of some people’s shopping experience.

He said as a scenario, “I can get the gallon of milk for $4. I can get a half gallon for $2.50. Now the half gallon is less expensive but there’s obviously less of it. It’s not as good (of) a value, but it leaves me more money in my pocket right now. How much milk am I going to use over the next week?”

The decision fatigue that goes with making these kind of essential decisions has a real impact on people’s ability to perform well in school, at their job, and as parents.

Myrick said, “Its got to be about raising wages and lowering housing costs…Those are two ways to make sure the grocery bill is not as daunting…”

Aside from the triad of nutrition, housing, and wages, there’s one more thing that Myrick said should be considered when addressing food insecurity.

He recounted what it was like as a student to receive free lunch at school and be faced with the embarrassment of being waved through the lunch line every day with his tray of food.

“You go through the lunch line and, at the end, the person would take your money or just wave you through. And being waved through in front of everybody, everybody knew that you couldn’t afford lunch,” he said. So he often skipped lunch or tried to wait until the end of the lunch period when there was no line to get a tray of food.

“I’ll never forget — it was a game changer in 10th grade — they changed the system,” he said.

The school added a keypad system so students could punch in an ID number and have money deducted from their accounts or be noted as a person eligible for free or reduced lunch. It made him look like all the other students, and he directly attributes that with a change in how he felt about going to school and a boost in his grades.

“Without little but thoughtful things like that to give people dignity, we can’t expect them to work their way out of poverty,” Myrick said. “I guess I’ll have to do some thinking on my own about what the city could do. Are there any small thing like that, that the city could do to help boost the dignity of folks.”